|

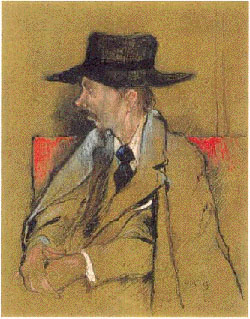

The Cypher

Press and Maggs

Brothers, London

'A great poet, a really great poet, is the most unpoetical of all

creatures.'

It is now widely, if not quite universally acknowledged that, when

in 1891 Oscar Wilde penned one of his most celebrated and typically

paradoxical aphorisms in The Picture of Dorian Gray, he - already by

this date London's most prominent litterateur - was referring to Enoch

Soames, perhaps of all his contemporaries the most unsung, and certainly

the quintessential figure of the 'Tragic Generation' of the Eighteen-Nineties.

But Soames, more perhaps than any other English man-of-letters, wrote

the poetry he dared not live; his heroic, once-and-for-all decision,

on that dim summer's day, now more than a century ago in June 1897,

was finally and irrevocably to live - or rather, to die - for the poetry

he no longer dared to write.

Whilst we who gathered in the all-pervading,

crepuscular quiet of the vast Reading Room of the British Museum a hundred

years thence put up but a poor show in response to his grandiose sacrifice,

we may salve our consciences and remember that, as Max Beerbohm wrote,

it was always fated to be thus. For Soames, real tragedy was too fine;

his métier, his fate was failure. Soames, we must always remember,

was a man whose terrible lack of judgement, sartorially as in all too

many other aspects of his tragic life, led him, after Heaven knows what

process of deliberation, to choose for his entry into the fiery kingdom

of Hell of all garments a water-proof cape.

And yet, nonetheless, regret we may . . . Had the newspaper library

with its precious store of literary reviews not been transferred to

the forlorn and banished wastes of Colindale. . . Had the tiny handful

of copies of the first edition of this present work not been fatally

delayed at the bindery. . . And when, in that moment of hushed anticipation,

when like the no-more-than half-expected stroke of some ancient clock,

he, the great poet, Soames himself appeared, had one of us - only one

of us - had the courage to approach him... How different things might

have been.

However, such regrets are but crystaline tears which fall upon the preterit

and are bootless; the moment has passed, and Enoch Soames will, in this

world at least, never know the true extent of his influence, or the

real esteem in which his remarkable œuvre has come to be held.

For those of us who remain, and who care, Enoch Soames: The Critical

Heritage, it is to be hoped, will provide a bridge between the triple

extremes of popularism, arcane scholarship and cultism to which the

poet, his work and his reputation have fallen prey. Here the ordinary

reader, as much as the earnest aficionado and the obsessive bibliomane,

may for himself re-discover anew some of the many facets of this complicated

figure.

Soames students have traditionally been hampered, not only by their

subject's mysterious disappearance, by the inherent unreliability of

witnesses and the extreme paucity of accurate records, but most seriously

by the small number of works our far-from-prolific author left behind.

It was as Dr. Johnson had foreseen: 'those authors whose reverence for

the public has hindered them from swelling their works with repetition,

or encumbering them with superfluities, and who, therefore, deserve

the praise and gratitude of posterity, are forgotten, and for the very

reason for which they might expect to be remembered'.

Enoch Soames, despite everything, will not be forgotten. If the critics

of his age, as well as many of our own who are blind to truth and beauty,

have misjudged and undervalued the quality of his work, a great mass

of the common people, both in England and abroad, have held or hold

still in their hearts the memory of this incomparable bard. Indeed,

it has been the truly global appeal of this most neglected of poets

that has proved so surprising ; contributions to this volume of celebration

have come, as so many devotees came to the Reading Room in 1997, from

the four corners of the globe. The size of the crowd which fiocked to

those celebrations to observe the centenary of his tragic and curious

end was unforeseen and unprecedented, their very presence a poignant

reminder of a desire to mark what Baudelaire might have termed that

'last glimmer of heroism in the face of decadence'.

Legion were the articles, programmes and features - in magazines, national

newspapers, and on the television and radio - which, in those hectic

days leading up to the 3rd of June, examined Soames's curious tale.

Experts gathered, talking heads discoursed, and new playwrights based

productions on the legend, whilst from Australia came an opera based

on the poet's life, which toured the towns and cities of Great Britain

where the name of Enoch Soames had never previously been heard. As we

now see, Soames's reputation as a literary figure of almost unparalleled

popular interest had only been fanned by the lack of critical attention

his work had received. Could it be that he had become, sadly too late,

a figure of private renown?

How many of us, gathered library-silent under Panizzi's great dome that

day, truly expected Soames to walk again among us? For how many of us

had 3rd June been merely a date we noted, much like Easter, transferred

from diary to diary, year after year, merely for its numinous symbolism?

And yet, against all rational expectation, on that day, there, in the

great Reading Room, he he was there; and we saw him. Soames, could he

only have known it, would have been proud to be in such a company.

For the rest, for some - those oldest habitués of the British

Museum - 1997 came too late, and they would never see Soames. For others

it came too soon; for them, denizens of a new and soulless Reading Room,

what can there be to look forward to now? But for those of us who were

there, we happy many, the words of Henry V at Agincourt still ring true:

We were there. And we saw it all.

|